SCHOLARSHIP FROM THE 19TH CENTURY TO THE 21ST

It is now commonplace within secular history and among sceptics to claim that the Book of Genesis is derivative from a regional corpus of Mesopotamian religious epics. This corpus includes the well-known Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 1800 BC), the Enuma Elish (c. 700 BC), the Eridu Genesis (c. 1600 BC), and the Epic of Atrahasis (c. 1600 BC), and others (but see section on historical challenges for more details regarding dating).

The Mesopotamian texts are properly considered to form a family on the basis that they:

-

- Arose from within the same geographical region

- Reflect the influence of the Sumerian culture

- Either directly quote from each other, or share similar narrative material

- Are written in one of the two major languages of the region, Sumerian or Akkadian

Secular historians and sceptics argue that (1.) the Book of Genesis has a late origin, (2) the Book of Genesis is derivative from this collection of Mesopotamian literature and not in an independent narrative category of its own, and (3.) aspects of these foundation stories arise as literary products designed to address politico-cultural pressures.

As an example of (2), Neil deGrasse Tyson claims in one episode of the 2014 documentary series Cosmos: A Space-Time Odyssey that the story of the flood in the Book of Genesis was a “rewrite” of the Mesopotamian stories about Gilgamesh. An example of (3) can be found in the argument made by the translator and Assyriologist Thorkild Jacobsen that the Enuma Elish might reflect a Babylonian consciousness of being a upstart, parvenu state whose success came at the expense of its Sumerian cultural progenitor. Since the Enuma Elish features younger gods slaying their progenitors, Jacobsen suggests this may reflect a Babylonian national psychology in which the new empire was all too aware that its advancement was in a sense patricidal.

From a secularist point of view the historical logic that sees the Book of Genesis as a Hebrew appendage of the Mesopotamian corpus is impeccable. Logically, any text that originates later in time must be dependent on those that came earlier rather than the other way about; the first writings of the Book of Genesis are considerably younger than the earliest Sumerian poems, ergo, it is concluded that the Book of Genesis derives from Sumerian poetry.

Moreover, the secularist historian usually assesses cultural power on the basis of military power. Thus, a popular story or text from a militarily powerful region of the ancient world were likely to be exported to less powerful regions beyond its borders, whereas the reverse was more unlikely. Weaker states in the ancient world did not typically exert strong cultural influence upon stronger states (though it is not unheard of, as in the case of Greek influence on Rome). Since the Assyrian and Babylonian empires were strong military and cultural powers, the sceptic or secularist maintains that they must have perpetuated their culture well beyond their immediate borders, and this is why their stories influenced their weaker, neighbour Israel.

Given these arguments, it is hardly a mystery to discover in the interpretations and conjectures (for that is what they are) of both ancient historians and sceptics the claim being repeatedly made that Hebrew scribes plagerised from Mesopotamian scribes. It is claimed that the Hebrew scribes borrowed from already-extant Mesopotamian material, radically rewrote it, and cobbled together their own version of the myth.

The second article in this series will look at these claims in more depth but it is sufficient to say that this claim does not hang from evidence. Any confident declaration that the Book of Genesis is microwaved Mesopotamian mythology is built solely on one thing: that is, there is a narrative resemblance between some accounts in the Book of Genesis and some Mesopotamian myths. We may term this approach to historiography to be “parallelism”, which amounts to the argument that if x resembles y, then y must be dependent on x. No other evidence exists for dependence outside of this argument.

Obviously the Christian historian strongly rejects this conclusion for reasons that will be further explained in the second part of this series.

Nonetheless, Christian historians must take care not to dismiss the secular historian’s conclusions outright. Most of the secular historian’s conclusions are reasonable and sensible (in the domains that do not touch the historicity of the Book of Genesis, at least), and a good many of his assumptions were indeed pioneered by Christian Assyriologists. Most of the conclusions held by the secularist are rational and proper deductions that any properly trained Christian historian would also conclude for himself.

Therefore, the orthodox Christian historian can agree with the secular historian that inter-dependence exists between the Mesopotamian epics. In other words, a Mesopotamian story like Gilgamesh in the Standard Babylonian version clearly evolved from the earlier Sumerian poems that mention Gilgamesh’s adventures, and we can trace this evolution through the cuneiform tablets.

The Christian historian has no need to reject the clear evidence of the development of these epics as if the fact that the Mesopotamian epics grew over time somehow means that the Book of Genesis is just another developmental branch on the tree. While sceptics certainly make this claim (and on this basis), we can cleave that argument apart by simply demonstrating that the conclusion is not even remotely logically inevitable. Again, this will be explored more in part two of this series.

Thus, we must (and do) recognise that the Mesopotamian epics evolved and expanded over time from a common Sumerian source. This evolution saw the stories split into different versions and grow with the telling.

The case of the flood story found in the Standard Babylonian version of Gilgamesh is a textbook case. The story unquestionably began in an oral tradition and then was converted into Sumerian poetry. During the second millennium BC the story experienced change, until it settled into a fixed and final form in the first millennium BC.

Tracing the cuneiform evidence, we see how earlier iterations of the story are far simpler and shorter. The flood story in Atrahasis is less than 70 lines long, even accounting for the lacunae. On the other hand, the final version of Gilgamesh is between 300 – 400 lines long and tells the story in florid, fanciful and extended detail with extra material about capricious gods and goddesses and their excessively emotional reactions to the flood they themselves unleashed. On the other hand, the earlier versions of Gilgamesh (the fragmentary “Old Babylonian” tablets) do not include the flood story at all to the best of archaeological knowledge.

The differences in detail between the stories across various works are substantial. The differences include so basic a detail as the name of the hero himself (was he called Atrahasis, Ziusudra, or Utanapishtim?). Moreover, these changes appear to be have been deliberate scribal decisions given that Gilgamesh quotes several lines verbatim from Atrahasis – which indicates the scribe had access to the earlier text – but yet gives quite a different account, even contradicting the earlier account in regards to the role of the principle deity, Ea \ Enki.

We can deduce from this evidence without any threat to the Book of Genesis or our intellectual integrity that an original flood story expanded over time within the Mesopotamian culture. Both the Christian and the secular historian agree here!

Where the Christian and secular historian disagree, however, is on the status of the Book of Genesis and how it relates to the Mesopotamian narrative family. The secular historian claims the Hebrew text is derivative because it is a later composition and contains narrative similarities to a range of Mesopotamian texts, not just of the flood, but of creation, and the confusion of the tongues and so on. The Christian historian rejects this conclusion for reasons explained in part two of this series.

The secular historian and Christian can agree, nonetheless, that a distinct genre of myth arose in Mesopotamia centred around a “sacred origins” story. Christians can also agree with the secularist that this story was probably transmitted from an exceedingly ancient oral tradition. Its appearance in numerous forms and in multiple sources in the area (and even outside of the area, such as Egypt) indicate that the story had a widespread currency and significance. There is further evidence of competition to “claim” the story, and stamp upon it a particular city’s deity.

Nonetheless, the Christian historian must insist on fairness for the Book of Genesis. Although the Book of Genesis was probably written at least two hundred years later than the earliest Mesopotamian tablets, this does not logically dictate that the Hebrew scribes sourced their material directly from the earlier Mesopotamian cuneiform texts as sceptics are wont to claim.

The fact that the Book of Genesis contains a tremendous volume of narrative and discursive detail found in none of the Mesopotamian epics; has a radically different cultural outlook; a radically different moral emphasis; a different narrative setting; and its narrative is firmly tethered within the recognisably natural world, all indicates originality and not mere derivation, a conclusion an honest handler of the sources would have to agree with. Indeed, the bulk of the material in the Book of Genesis is entirely novel. Moreover, the Book of Genesis actually violently disagrees with the Mesopotamian epics upon far more than that with which it agrees, to such an extent that the Book of Genesis may be fairly and properly said to present entirely new stories to those found in the Mesopotamian epics.

A Christian historian would argue therefore that the Book of Genesis does not belong in the Mesopotamian corpus of epics on the flimsy basis of some narrative similarities, any more than one should argue that the Islamic account of Noah belongs in the Mesopotamian corpus, or that legends of Robin Hood – the so-called “good thief” – is derivative from the New Testament that records a thief’s confession of Jesus.

Neither should we assume Hebrew dependence upon Mesopotamian tablets. That is an assumption without warrant. Certainly, if oral stories in traditional societies can be transmitted for thousands of years, and can even continue to be transmitted despite the freezing winter of an alphabetic culture that continually longs to standardise stories, so too could oral transmission provide a source for the Hebrew scribes, as we will see in part two of this series.

As is usual within sceptical, secular history, texts of the Old Testament are generally pulled forward in time to make them less ancient (in the same manner that secular historians usually push the texts of the New Testament forward in order to move them further from the time of the events they narrate). By massaging the dates of the texts, the overall effort is to try to make them seem less historically reliable and safe. The Book of Genesis has most definitely been subject to this sort of process.

Since the late 1700’s, and particularly during the sceptical and turbulent scholastic upheavals in the 1800’s, critical scholarship has come to claim that the Book of Genesis contains composite sources within the text, the so-called J, E, and P sources. Since the 1970’s, a great deal of debate has circulated around this documentary hypothesis with some scholars challenging the dating of the three supposed sources, and others seriously challenging whether the sub-sources even exist. Certainly, there is no external textual evidence for these sources, and so these critical claims rest atop successive accretions of assumptions, assertions, conjectures and projections.

In any case, critical source analysis allows secular ancient historians to shave many centuries from some material in the Book of Genesis. Following the textual critics, some historians date some aspects of the Book of Genesis as late as the 5th century BC, and other aspects only as early as the 10th century BC. In contradistinction, the nearly-universal and ancient attestation of the Church and of the rabbinical scribes is that the Book of Genesis was written by Moses sometime around 1400 BC.

It does not help that secular historians frequently display a distinct and peculiar prejudice against the Book of Genesis, especially in regard to its relationship with the Mesopotamian epics. This bias is uncovered by assumptions that are appear to be rooted in a desire to flatten the Book of Genesis into the general blend of Mesopotamian myth.

For example, in his commentary on the Atrahasis, Professor Mark asserts that the hero of the epic, Atrahasis, was directed by the gods to take “two of every kind of animal on the ark” in order to preserve life. Yet neither the existent tablets of Atrahasis nor its older progenitor Sumerian text (the Eridu Genesis) say anything about the number of animals taken on the boat. If anything, the Eridu Genesis suggests that only a sub-set of animals were taken on the boat since it refers several times to “small animals”.

Both the Atrahasis and the Eridu Genesis (above) are fragmentary tablets with sizeable lacunae spaced throughout their narrative – that is, missing lines or gaps in the text. Lacunae appear at precisely the points where the heroes board the boat. In notes on these lacunae the translators have sought to supply probable narrative content, but oddly enough in some cases have relied upon the biblical Book of Genesis to do so. This is strange because it is interpolating details from a supposedly less ancient text that has also supposedly been subject to centuries of Hebrew revision, back into a more ancient one. The overall effect of these editorial notations in the gaps of the tablets, of course, is to suggest similarities between the biblical text and the Mesopotamian epics for which there is no evidence outside of translator whimsy and conjecture.

In any case, not once but twice Professor Joshua J Mark asserts in his commentary on the Atrahasis that two of every animal was loaded on the boat, when this is most definitely untrue. He makes this error, it would seem, in his rush to exaggerate the similarities between the deluge accounts and thereby minimise any originality of the account found in the Book of Genesis. This bias is more fully developed later in his article where he devotes a considerable amount of space to claiming that traditional Christian historiography has been overturned on the basis of “irrefutable evidence”, though he provides no hint of what that irrefutable evidence might be.

CONTEXT, ORIGINS AND CHALLENGES

Mesopotamia is a diagonal territory that extends from the north-eastern corner of the Mediterranean sea in southern Turkey all the way down to the top of the Persian Gulf on the eastern side of Saudi Arabia – roughly following the rivers Tigris and Euphrates which flow through the area.

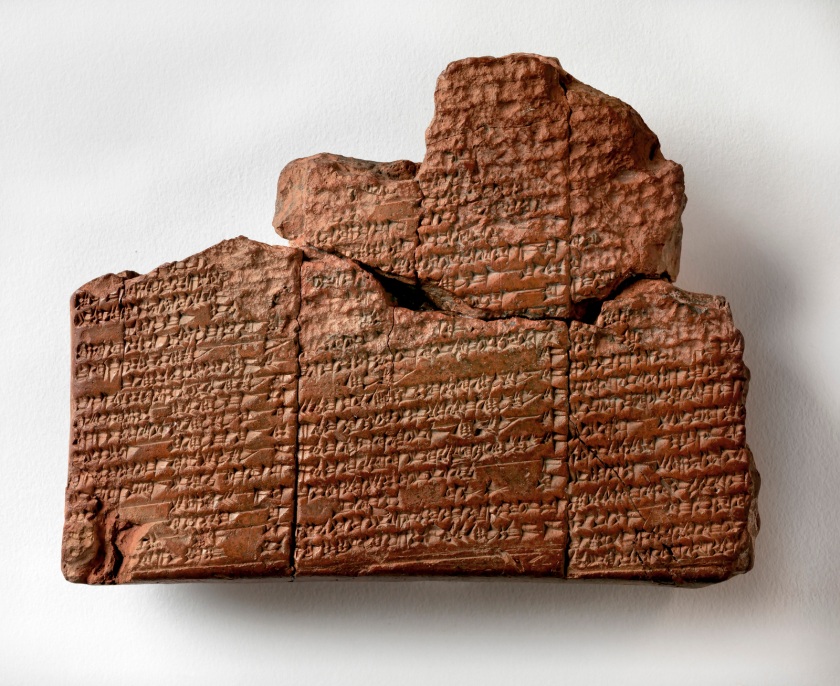

Ancient Mesopotamia gave birth to a number of cultures, powerful city states, and “superstate” empires. The earliest was the Sumerian civilisation located in the south of Mesopotamia. It was the Sumerians who developed a method of imprinting symbols on wet clay tablets called cuneiform. A wedge-shaped reed would be used by a scribe to make impressions on the clay, and the final product would then be baked. Unlike perishable materials like papyrus or vellum, fired clay is hardy. It is not vulnerable to mould or fungus, does not quickly decay outside of a narrow band of humidity, for example, neither is it subject to mechanical fatigue like a roll of vellum that is repeatedly handled.

The Sumerian civilisation is considered to be one of the oldest in the world if not the oldest, even more ancient than that of the Egyptian or Chinese civilisations. Certainly, the Sumerians themselves were conscious of their own antiquity and claimed for themselves the oldest city in the world, Eridu, possibly founded as early as 5400 BC. Significant city states emerged in Sumer, some recognisable to a reader of scripture, such as Ur.

Around 2300 – 2400 BC, the Sumerian civilisation was subsumed into the Akkadian Empire by its first ruler and conqueror, Sargon of Akkad who defeated the Sumerian city states and welded them into what is sometimes considered the world’s first empire. Peculiarly, this empire united both speakers of two languages, Sumerian and Akkadian, making it quite possibly one of the first bilingual societies.

Eventually the upstart Akkadian language displaced its Sumerian rival, and Sumerian became the language of scholars and priests in a similar way to which the Latin language has functioned until recently.

Inevitably, the Akkadian Empire crumbled and divided into the Assyrian Empire to the north and the short-lived Babylonian Empire to the south. Both empires spoke Akkadian, although differences evolved within the language. But in time, with the rise and fall of the states in the region, the Akkadian language too suffered the same fate as its Sumerian predecessor, and became the language of scholars and religion until it was absorbed by the Aramaic language that would later be spoken by our Lord.

The transitions between these periods are marked with countless upheavals. There are numerous wars, the rises and falls of powerful and semi-autonomous city states, competition between rival rulers and dynasties, and climactic change (the city-state of Ur, for instance, was at one time situated on the edge of the Euphrates whereas its ruins today are nearly 20 km from the river). Empires expanded and contracted, and there were sudden reversals of national fortune. There are records of periods of extreme mismanagement leading to famine, as well as some periods of relative stability. Eventually, the region was invaded by powerful outsiders in the form of Greeks and Romans.

During this time, the Mesopotamian culture produced large repositories of cuneiform texts which have been unearthed from “libraries” in the ruins of ancient cities. These texts cover everything from law to medicine to religion. Primarily they cover administrative and legal matters, but a sizeable minority address sacred matters. Some of these religious texts are the earliest written material known to history.

The oldest, predictably, are written in Sumerian while later texts are written in Akkadian. Some, like the Enuma Elish are focused on Babylonian culture and supremacy, while others, like the Epic of Gilgamesh lionise actual historical rulers such as King Gilgamesh who once ruled the Sumerian city state of Uruk.

The interplay between this crackle of variables – or, perhaps better, a regional cauldron of pressures and forces – presents all of the linguistic and interpretive challenges usual to the study of ancient history, with an additional set of difficulties that arise from exploring ancient sources that contain elements of the narrative material sacred to the orthodoxies of the world’s monotheistic faiths. For a sceptical secularist, the opportunity to cast doubt on those orthodox certainties is often irresistible.

The task of the scholar, then, involves:

- Properly dating the physical texts

- Working out the inter-textual relationships between the sources

- Understanding the relationship between the text and its society or culture

- Properly translating the texts

- Piecing together and interpreting fragmentary texts

- Properly placing variants of the texts into a larger sequence

Despite ringing declarations of “irrefutable proof” by Professor Mark (who is not, it appears, trained in history but rather in philosophy) and sceptics for whom the primary motive of their writing is often to do a simplistic demolition job on the Book of Genesis rather than really engage in complex and meaningful history, none of these tasks can be completed easily or in full. Conjecture is always the constant companion of the ancient historian. Beware anyone who speaks in triumphal tones about history far distant!

The complexity of the work is substantial.

For instance, task one (1), though it is the most basic task of the historian, is not at all straightforward when it is considered that the physical remains – in our case, the cuneiform tablets – are not the same thing as the content. Or, put another way, just because a historian can date the tablets themselves does not mean they have also dated the stories told by the tablets although this mistake is frequently made by the layperson or the sceptic. It is important to recognise these two elements are not congruent and hot debate surrounds the age of the various Mesopotamian epics.

To use a modern example, if future historians were to unearth a black and white movie on DVD in the rubble of our civilisation they might readily date the movie to the late 20th century or the early 21st century on the basis that it was distributed on a plastic disc. They would not, however, be able to date the content so easily. Many complications present themselves even in so brief a span of time as cinematography has existed.

For example, the movie might have been filmed in black and white for effect by modern arts students, or it might be a restored copy of a wartime cinema flick. It might be in black and white because it is a pirated copy of a colour edition, or it might be a composite production using material separated in time by a hundred years (e.g. 1920’s material enhanced with special effects from the year 2020).

Even without supposing these elaborate possibilities, the future historian would still have to wrestle with the fact that black and white movies were commonplace for at least thirty years, and so the movie could fit into a wide scope of time.

The same complexities are not just present but all the greater for the Mesopotamian epics. It is a substantial challenge to date the physical cuneiform tablets on the basis of clues in their language, or references to lists of kings, or the strata in which they were found, or the dialect in which they were written, or their location relative to other tablets, or distinctive scribal flourishes and colophons. The result is that to even speak of singular dates for the physical material is either misleading or flatly ridiculous. This has not, however, stopped many sceptics and websites giving definitive dates for this or that clay tablet and assuming that its content is as old.

One of the world’s foremost experts in the Gilgamesh epic, Professor Andrew R. George, spent 16 years collecting all extant sources into a two volume critical edition. This seminal work includes George’s first hand study of all of the cuneiform tablets and the creation of reliable pen and ink copies of the cuneiform script. This definitive work, published in 2003, describes the explosive trend of the previous 70 years since the last academic edition by archaeologist R. Campbell Thompson who excavated Ur and later Nineveh in 1931. New discoveries have greatly multiplied the numbers of sources for the Gilgamesh epic. For example George points out that in 1930 just four fragments older than 1000 BC was known to Thompson and other scholars, whereas by 2003 archaeological effort had uncovered 33. In 1930, 108 first millennium BC fragments were known, whereas by 2003 this had nearly doubled to 184.

The Standard Babylonian Version compiled by George Smith in the late 1860’s, which is still the most common model of Gilgamesh for scholars since, was pieced together from between 15,000 fragments to 30,000 fragments (this latter figure supplied by Morris Jastrow and Albert Clay in 1920, both experts in their era). The avalanche of new discoveries of fragments of Gilgamesh from all over Mesopotamia, with wide differences in their dates, has led to an increasingly complete version of the epic. Nonetheless, it is constituted from a Frankenstein assemblage of tablets from a range of places, dates, and in varying conditions.

Certainly, as Professor Andrew George points out, the second millennium BC tablets are fragmentary and even the first millennium tablets are far from complete, but enough text survives to allow a provisional outline of its evolution. It is clear that the very fragmentary Old Babylonian tablets differ markedly from the earliest references to the character of Gilgamesh that appear in the most ancient texts, these being the five Sumerian poems that feature “episodes” of Gilgamesh’s adventures.

Thus, in some ways the crude dating of the tablets is the easiest task that faces the secular historian or archaeologist, for it is a far more complex matter to date the stories themselves and trace their evolution. The transmission of the stories from the five Sumerian poems, into the disparate and composite Old Babylonian set of fragments with numerous differences, into the standardised imprints of the epic that now comprise the Standard Babylonian Version shows numerous changes. Of course, why the epic changed is open to conjecture, as is the question as to where the expanded material came from.

It is agreed that the older works bear the unmistakable features of an exceedingly ancient oral source, but even so, by the time they were imprinted onto cuneiform tablets the very medium itself bears witness to the fact that a scribal school had emerged. The Sumerian scribes undoubtedly would have modified the oral form of the text – perhaps polished it, or added their own personal touches, or enhanced it with more drama, or refined it to make it more suited to high-class consumption than it might have been in its minstrel or popular origins. Andrew George suggests that the oldest Sumerian poems featuring Gilgamesh were probably forms of court entertainment whereas by the first millennium the extended form of Gilgamesh was a standard copy-book.

Once we reach the frontier of the cuneiform texts, what lies before the historian are the uncertain oral mists of time. At this point, tracing the story is impossible. The origins of the flood and creation accounts are all but impossible to pinpoint or explain in the absence of any evidence, and in the face of the notorious difficulties of accessing oral traditions. We may say that the stories arose from the region, but we cannot say much more than that. Nonetheless, it is agreed – both the Christian and secular historian can say together – that a deep, pervasive, and culturally-significant oral tradition existed which must originally have featured a flood story (or stories), and a creation account.

Task five (5) is a permanent challenge. Many of the cuneiform tablets are cracked or splintered; some exist in a slurry of shards with the texts assembled from different copies; and lines of text are missing – sometimes many lines of text – from even the most complete tablets (e.g. the Enuma Elish, though largely pieced together from multiple fragmentary copies, still has large numbers of lacunae sprinkled throughout its seven tablets, and substantial lacunae obliterating much of Tablet V).

As mentioned already, tasks two (2), five (5) and six (6) are necessarily given that there are several versions of some of the stories. The flood narrative, for example, greatly expanded over time by the time we get to Tablet XI of Gilgamesh in the Standard Babylonian Version. The same narrative appears only in a far briefer form in older Sumerian poetry.

Task four (4) is a perennial problem that will last as long as time itself. As with the translation of any long disused language, difficulties exist when identifying the meaning of ambiguous terms and words. A really full and perfect understanding of some ancient texts may well be impossible to ever attain. It is one thing to decipher words themselves, it is quite another to grasp shades of meaning, contextual allusions, subtleties, word play, literary images, jokes, and the rest of the panoply of meaning conveyed by text. All texts, after all, assume a reader who is thoroughly immersed in the cultural context. Outside of that cultural bubble, meaning starts to be lost. Anyone who has ever casually used a native idiom in another country will be familiar with the shedding of meaning, even when both speakers share the same language!

This is sometimes evident in translations of Gilgamesh, which are subject to correction by later improvements in understanding of Akkadian. Translators are sometimes swayed by their own points of reference in their translation choices. For instance, it is clear that more than a few translators of Gilgamesh were heavily influenced by the Bible – whether from pure motives or perverse is irrelevant – and therefore sometimes translated phrases from the Gilgamesh tablets to resemble the narrative they knew in the Book of Genesis.

For example part of the flood narrative of Gilgamesh tells how his boat at lasts comes to rest. Most translators speak of it alighting on “Mount Nimush” (modern Mount Nasir) in similitude of the “Mount Ararat” mentioned in the Book of Genesis.

Yet the underlying Akkadian word is more directly rendered “hill” (possibly “mound”), not mountain. In the Sumerian language although the word is directly translated “mountains”, it is well understood that this was intended to convey the meaning of “foreign country” since the Sumerian civilisation was bordered by a mountainous region. An alternative translation, therefore, is that the boat settled in the “country of Nimush”, not on the mountain of Nimush.

Translators have likewise adopted linguistic license when translating the text where Gilgamesh leaves the boat and makes an offering. Most older translators of the text have written it in such a way that it refers to Gilgamesh making a sacrifice/offering/pouring out a libation “on the peak of the mountain”. But the original text unquestionably contains the word ziggurat which older translators have simply deleted from the text.

Ziggurats were the religious temple towers or elevated platforms commonly constructed in Mesopotamian cities. They had the rough appearance of a flat-topped mountain.

There is no good reason to discard the word ziggurat from any English translation. Older translations have deleted the word on no greater authority than merely following the precedent set by previous translations. They have argued that the word “ziggurat” is mere a textual redundancy or scribal flourish that refers to mountains, and since the Book of Genesis refers to Mount Ararat, they interpolate it into their translation.

But what kind of argument is this? It is the mere assertion of parallels; the assumption of a metaphor that is not at all apparent; and with zero evidence a claim that the original writer used the word ziggurat in a disposable manner.

In recognition of the weakness of this older view, newer translations have restored the word ziggurat and now speak of Gilgamesh making his offering “in front of a mountain ziggurat”. One translation uses the phrase “on top of a hilly ziggurat”. Both translations at least do a more credible job of presenting the underlying language without the assumptions and biases made by older translators, who, when faced with a linguistic ambiguity or oddity, seemed to err on the side of making Gilgamesh more closely resemble the narrative in the Book of Genesis.

The above tasks of the ancient historian are never done, which means that we can never achieve absolute certainty about aspects of these texts. Assumptions always have to be made. Ancient history invariably involves making assumptions.

Some of the resulting conclusions from these assumptions are decidedly sensible and there are points upon which both secularist and theist would agree. Other conclusions, however, are reasonable and rational only if one has a secular worldview prior to working with the historiography. Thus, demands to accept the products of such secularism is essentially tantamount to demanding a person should also accept the secularism that gave rise to the conclusion.

For Christians whose worldview is fundamentally supernatural such assumptions and conclusions must rejected from the outset. A believing, orthodox Christian can survey the world of these tablets and stories, of ziggurats and dysfunctional families of deities, and come to very divergent conclusions that are also historically reasonable. We are not doomed to disbelief, or chained to scepticism, or must lapse into intellectual dishonesty as the only outcome of investigating the ancient past, which sadly is the presumption of too many secular historians, irrational though it actually is.

Hi, I hope and pray you and your family are well. I have really enjoyed your insights in the past and regularly check back to see any new posts. Thank you for what you are doing! All the best, Lourens

LikeLike